Over the past couple months I’ve been helping a potato company get their finances in order.

Quick backstory: When I was introduced to this company via an online freelance network, it was listed as a tomato company. I was busy, but my interest was piqued because I grew up raising tomatoes on my Dad’s produce farm.

I applied for the job and went so far as to list “familiar with raising and marketing tomatoes!” (yes, with the exclamation mark) in my brief application. Much to my embarrassment, on the interview call I realized they raised potatoes, not tomatoes.

It wasn’t a total fail, I guess, because they hired our firm anyway.

This company faced a problem I’ve seen many times. They had a good team of bookkeepers and even a good controller, but no one to “pull everything together” at month end to generate accurate financial reports. Some companies can basically get away with this deficiency, but not this one.

The reason good bookkeeping alone didn’t produce useful monthly financial reports was largely due to one little account. This account swung the bottom line up and down by literally millions of dollars.

The account was called:

Investment in Growing Crop

Maybe you’re thinking, Is this a niche article for farmers?

No it isn’t – keep reading.

Before I explain this account, let me say I was impressed to even find it in their accounting system. Very few software programs have an account like this, and even fewer have functionality to use it.

The company rotated plantings in several states to extend the potato harvest. Like most crops, potatoes require substantial upfront cost in land rent, tillage, seed stock, fertilizer, and irrigation. All these costs happen long before a single potato is sold.

This company also had a side project growing seed potatoes, which I learned is quite a process. A good batch of seed potatoes takes 3 or 4 years until they’re ready for market. Yes, you read that correctly.

If the upfront costs of these crops were simply expensed on the profit and loss reports, the company would have many “ramen noodle” months during the growing season. “Ramen noodle” is a technical accounting term meaning “big loss.” These months would have $0 sales, but thousands (even millions) of dollars of expenses. Based on their financials, the owners would be destined to eating cheap ramen noodles in their dimly-lit hut (if they had a hut).

Then, after the potatoes were packed in warehouses and sold to stores, there would be months of millions of dollars of sales and very few expenses. The accounting term for months like those are “private jet” months. I think you get the picture.

The way to avoid this roller coaster is to not use an expense account, but instead transfer these costs to a balance sheet account like “Investment in Growing Crop.” As mentioned, this company’s software already had it all set up. It just wasn’t accurate.

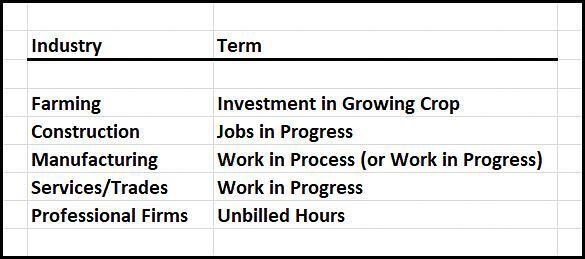

Important note: Most companies in most industries need an account like this. The terminology varies by industry, but the idea is the same.

Here is a quick guide:

The shorthand terms are “WIP” (for work in progress) or “JIP” (for jobs in progress). All of these terms refer to the same thing: Costs related to a project, crop, or asset that will be sold in future months.

Pro tip: If you ever find yourself interviewing a CFO for your company, and want to sound like an impressive business owner, try offhandedly injecting “WIP” or “JIP” into the conversation.

How to accurately track WIP and JIP is an extremely complex topic that would take months to truly explain.

In short though, if your company has costs that won’t produce sales until a future month, you hold those costs as an asset on the balance sheet until the month the items (e.g. potatoes) are sold. In that month, the costs come off the balance sheet and become an expense against sales.

It’s very similar to Walmart buying a truckload of shoes and holding them in inventory until the shoes are actually sold. Walmart does not expense the shoes when they buy them, they expense them when they sell them.

I know. It takes a little to process this.

A potato farm or construction company tracking WIP is essentially following Walmart’s shoe example.

This “simple” procedure keeps profit consistent across all months and avoids the ramen noodle/private jet boom-to-bust cycle.

One Huge Problem

Since this concept is absolutely HUGE in most industries, how many accounting software systems are set up to automatically handle this?

Answer: Basically zero.

The potato company was unusual in that they actually had impressive software to handle this. But even with that, it still took an experienced human to make it work.

This is especially true for companies that recognize profit each month on a project as it goes along. Potato farmers usually wouldn’t do that. It just doesn’t make sense to record the profit from the growth of the potatoes each month. Better to wait until the end, when the potatoes are sold, to recognize any profit.

But companies in construction, manufacturing, the trades, consulting, etc. do it all the time. They record profit each month on each job, as the jobs progress.

Often in those industries, there is the added complexity of the customer making payments on the project as it goes along. Since these payments usually do not line up perfectly with the company’s actual expenses, it just muddies the picture further.

What is the Solution?

What comes to mind is Winston’s Churchill’s famous quote:

“I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat.”

If you don’t like dealing with WIP, either:

- Keep your business so small you can keep track of everything in your head, or,

- Do each job/project in one day and give the customer an invoice at the end the day, or,

- Find a simple (from an accounting perspective) industry like retail.

Another option is to intentionally arrange your business to make the accounting easier. Usually that’s a bad idea, but sometimes you have to do what you have to do.

I’ve personally done this at Hoover Financial. I try to catch up all of our costs (payroll, subcontractors, etc.) monthly. I do this exactly through the last day of each month. On that same day (the last day of the month), I also send an invoice to each customer that exactly charges them for the work done in that month, through the last day of the month.

This process puts all related costs and sales in the same month, even though we often work on multi-month projects. Granted, we can’t do this for every project, so we still need a small WIP account, but this procedure eliminates 90% of the battle.

If you simply have too many moving parts, or a production process that cannot be split into granular months, then there is nothing to do but invest in carefully tracking Work in Progress at the end of each month. Even if you need to outsource this step, it is generally well worth it.

This one step can take a maddeningly gyrating profit and loss statement and smooth it right out. But trust me, it will be done, at least in part, by a human.